Self steering is one of the most important considerations for solo sailing and any sailor who is preparing to embark on an offshore voyage. Many people who have never sailed alone believe that single handed sailors spend entire passages glued to the helm, spending weeks on end behind the wheel through heat and gales, only pausing for brief moments to grab a snack or go to the bathroom. Thankfully for solo sailors, the reality is usually quite different.

Most solo sailors have indeed been forced to steer for prolonged periods of time at some point in their careers, but the reality is that most lone voyagers use a windvane or autopilot to steer as much as possible, freeing their time up to take care of the boat and enjoy the passage. It’s one of the greatest beauties about blue water sailing vessels that you can get the boat to sail herself most of the time, which allows the captain to spend his hours navigating, handling the sails, reading, cooking, fishing, singing poorly at the top of their lungs, and enjoying the rare freedom that is only known to people who have been hundreds of miles from the nearest human being.

While preparing to write this guide, I asked eight highly experienced single handed sailors what was the most important piece of equipment they took on their expeditions, and all of them agreed it was their self steering systems.

Whether you choose to equip your vessel with an electric autopilot, a windvane, or simply use sheet to tiller steering techniques, it’s absolutely critical to the success of your voyage to have some kind of self steering mechanism in place to keep your boat headed in the right direction while you sleep or tend to the boat.

In the third and final part of our solo sailing series, we will take a look at self steering for single handed sailors, beginning with a brief history of self steering techniques, moving on to explore different types of self steering available to sailors today, and finally covering how to decide what self steering system is best for you.

A Brief History of Self Steering Techniques

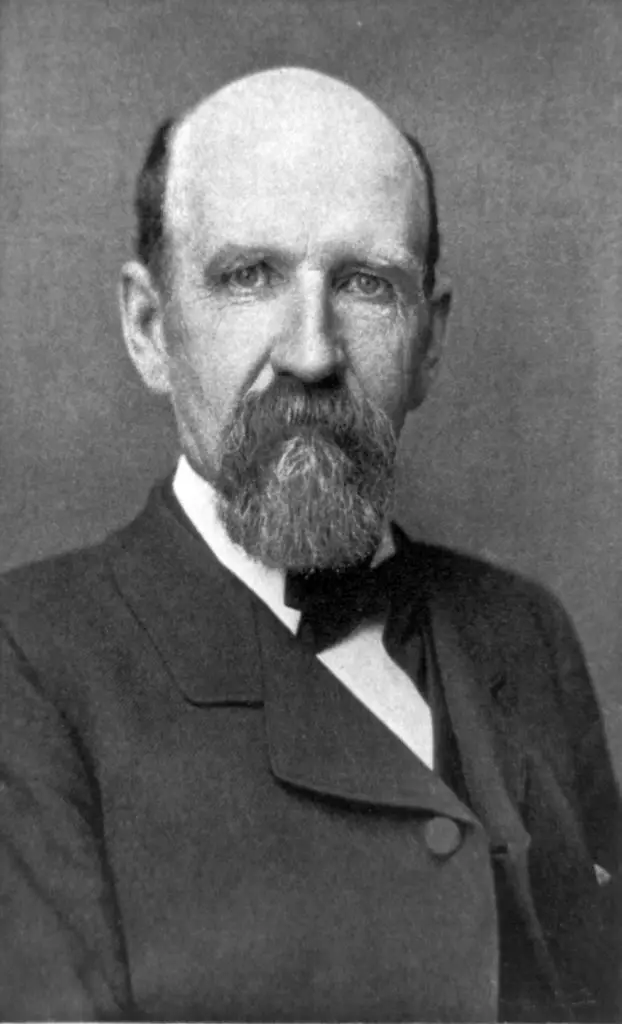

The great pioneer for self steering techniques for solo sailors was Joshua Slocum, an American sailing ship captain who witnessed the dying days of the great age of sail and went on to become the first person ever to sail around the world alone. Slocum’s circumnavigation was completed in the early 1900’s on an old fishing vessel (called the Spray) that he had refitted for the voyage himself. At the time of Slocum’s solo circumnavigation, sailing alone offshore was so rare that he was often accused of murdering and eating his crew at sea.

When Slocum left Boston to sail around the world, it was agreed upon among sailors that every vessel needed at least one or two crew members in order to keep watch and steer the vessel while the captain slept. Even captains of small fishing or merchant vessels that were only at sea for a day or two at a time brought along a second mate to help handle the boat. Nobody could fathom why he would want to do it alone.

Slocum claimed that the Spray, which in addition to having no crew was also engineless, could hold a steady course on just about all points of sail. He would set the sails so that the boat was well balanced, lash the wheel to account for any lee helm or current, and lie down to sleep – sometimes for hours at a time.

There were instances that he didn’t touch the helm for days at a time, like when he fell violently ill from food poisoning off the coast of Spain. Slocum crawled down below and curled up on the cabin floor in extreme pain. At some point he looked up the companionway and saw a “ghost captain” who he believed had taken control of the wheel to keep the Spray clear of rocks.

Slocum recovered and eventually completed his voyage, returning to Boston three years after his departure. The voyage made him an instant celebrity, and Slocum wrote a book about the voyage which is still in print over a hundred years later. His voyage inspired other solo sailors to attempt the same feat, and each of them dealt with self steering using their own techniques.

As more sailors attempted to replicate Slocum’s solo voyages, it became apparent that not all boats had the same natural ability to hold a steady course as the Spray. Many vessels will steer themselves quite well with the wind forward of the beam, but as the wind moves aft, they tend to become more temperamental, rounding up into the wind. Various techniques were tried to remedy this problem of self steering downwind, often using twin jibs that were connected to the helm via a series of blocks and lines. This technique was used with varying degrees of success, but it never came close to competing with a contemporary windvane or autopilot with regards to ease of use and reliability.

By the 1950’s, solo sailing was taking off as a major sport for challenge seekers and adventurers. A single handed transatlantic race was conceived (which later became the OSTAR race) from England to the United States and solo sailors and their exploits became a regular feature on newspaper headlines from London to New Delhi.

Despite all this interest in solo sailing, self steering was still the greatest single problem for lone sailors. Then Blondie Hastler, one of the competitors in the early races, came up with an invention that would change the world of solo sailing forever.

Hastler designed the first self steering windvane, a device which uses a small sail and auxiliary rudder to keep the boat sailing on track based on the wind direction (see the section “Windvanes” below). Windvanes immediately took off, and within a year or two of Hastler revealing his invention to the world they were already extremely popular among solo and double handed sailors. In 1968, when the Golden Globe round the world yacht race was held, each competitor had some version of Hastler’s self steering system.

Soon, the first commercial units hit the market, and by the 1970’s there were over a dozen manufacturers of windvane self steering units. The early designs had various issues, but each year brought new innovations, and today there are a number of highly proven windvanes available on the market. Some models are strong enough to be guaranteed to hold up for an entire circumnavigation, and I have been told of one Australian circumnavigator using the same Aires windvane for ten different round the world voyages.

Windvanes serve their purpose very well, but the limitations to windvane self steering became more apparent as racing sailboats got faster, in some cases moving faster than the wind. The problem with using a windvane to hold a course when you are sailing faster than the wind is that the apparent wind direction becomes so far from the true wind direction that a windvane cannot hold a steady course. That’s why you never see a windvane on an IMOCA 60 or a 100 foot racing trimaran.

The first time an electronic autopilot was used as a means of self steering for an ocean crossing was in 1936, when Marin Marie traveled from New York to La Havre on his 13-metre motor vessel Arielle. Marie used a primitive version of an electric autopilot to varying degrees of success on his voyage, but it took many more decades for them to become regularly used by boaters. Today, electric autopilots have become the most popular choice for self steering, although windvane self steering remains a favorite for hard core offshore voyagers.

Windvanes for Solo Sailing

A windvane is a piece of equipment that is mounted to the transom of your vessel which uses a small sail and miniature rudder to steer your boat according to the wind direction. The windvane is set so that the wind passes on both sides of the vane. When the boat veers off course, the wind pushes on the side of the vane – causing it to pull on lines which are connected to the steering system via a series of blocks. The whole setup uses no electricity and can operate in anything from six or seven knots of wind to a full blown gale.

There are many models of windvane available on the market, but they are all based on one of two primary types – a servo pendulum or auxiliary rudder. Servo pendulum windvanes use lines connected to the ship’s primary rudder to steer the vessel. Auxiliary rudder windvanes use a smaller separate rudder to steer the boat with the primary steering locked off amidships.

The advantage to a servo pendulum style windvane is that it can be much smaller and better concealed than an auxiliary rudder style unit. In the case of Cape Horn windvanes, the unit can be made to fit with the lines of the vessel so that you barely notice it’s there at all. Cape Horn windvanes also have few moving parts that can break, and they come with a warranty for 28,000 miles or a complete circumnavigation.

The advantage to the auxiliary rudder design is that they don’t need to be connected to the main steering system, and they can also be used as emergency steering if the primary rudder is lost. If your vessel has hydraulic steering or is equipped with dual helms, it’s a good idea to choose an auxiliary rudder type windvane, as they operate independently of the primary steering. This also gives the added advantage of not requiring lines to cross the cockpit, as is needed with most servo pendulum style windvanes.

Electric Autopilots for Solo Sailing

Most cruising boats today are equipped with some type of electric autopilot (which uses a compass course or GPS coordinates to steer the vessel). The reason for this is they are relatively cheap when compared to the cost of a windvane, they are easy to use, and they can usually be installed without any significant changes to the vessel. They don’t change the appearance of the boat and don’t require a large external frame mounted to the transom.

On the other hand, electric autopilots often use a lot of electricity to operate, and are notoriously prone to breakages. I have found autopilots to be the second most common thing to break or malfunction during an offshore passage, after combustion engines.

Of course, if you plan to be doing a lot of motoring, or if you have a racing boat that is capable of sailing faster than the true wind speed, an electric autopilot is the only way to go.

There are three options available for electric autopilots – units that steer using an adapter that attaches to the wheel, units that use a hydraulic ran to move the rudder, and tillerpilots that connect directly to the tiller for smaller vessels. Tillerpilots are by far the cheapest option of the three, and they can be connected directly to the auxiliary rudder or servo pendulum on a windvane to steer a larger boat.

While autopilots are no replacement for a windvane for a long offshore voyage, I believe that an electric autopilot, paired with other self steering options, is an important piece of equipment for modern day solo sailors.

Sheet to Tiller Steering and Other Alternative Techniques

Even on vessels equipped with a windvane or autopilot, it’s important to have a back up plan in case of equipment failure, especially for solo sailors. Prior to departure on your solo passage, it’s a good idea to practice balancing the sails and seeing how your vessel behaves with the wheel lashed on different points of sail.

One alternative method for self steering is sheet to tiller steering, where one of the sheets (usually a jib sheet) is led to the tiller and bungee cords or elastic tubing is used to create some counter tension. This technique doesn’t work for every boat, but it’s worth experimenting with in case your windvane or autopilot breaks at sea. Of course, this only works for boats that have a tiller rather than a wheel.

On solo deliveries, I have often found myself on a vessel with faulty self steering gear. Usually I end up finding a way to balance the boat under sail while upwind, but I have had little luck keeping most vessels on course off the wind. That’s when I end up experimenting with sheet to tiller steering, or bracing myself for long hours at the wheel.

What’s the Best Self Steering for My Vessel? – Making the Final Decision

Investing in the proper type of self steering gear is one of the most significant decisions that you will need to make before embarking on a solo passage. It’s important to read everything you can find about the types of self steering that are available, and talk to other boaters with a similar type of vessel. Ultimately, the ideal setup depends on your size and design of vessel, type of primary steering onboard, and where you plan to sail.

Personally, I believe that pairing a windvane and a small tillerpilot is the best setup for most mid size cruising vessels. The windvane can be used to steer the boat under most sailing conditions, and the tillerpilot can be attached to the servo pendulum or auxillary rudder to steer the vessel while motoring or in light winds. If one system breaks, you can use the other to get to port and make repairs. I think the best choice of windvane is one that also can function as an emergency rudder, like the Hydrovane or Sailomat 3040 systems. That way, you can kill two birds with one stone.

I chose a Hydrovane auxiliary rudder style self steering system for my own boat, and it has performed wonderfully thus far. I would recommend the same to any solo sailor with a mid size cruising vessel.

SailAndProp.com is the best place online to find all the information that you need to plan your future boating adventures. From choosing the best type of self steering gear to planning your route across the oceans, SailAndProp.com has got everything you need to hit the water with confidence. There’s no better way to keep up to date on all our latest boating info than to sign up to our newsletter, so don’t forget to subscribe today!